By Jonathan Tepper.

For the past few months, I’ve been trying to solve an economic puzzle: why are wages growing so slowly despite a growing economy and a booming stock market?

Workers are productive and helping the economy grow, yet unlike previous economic expansions, we are hardly seeing big increases in wages. Instead, companies are sitting on their cash or giving it back to their shareholders through dividends and share buybacks.

The answer of why wages are not growing mattered a lot to me. A few years ago, some friends and I started Variant Perception a company that predicts the ups and downs of the economy using leading indicators. Before growth or inflation turn up and down, there are generally clues that tell you what is coming. For example, building permits provide a good warning sign that growth will turn up or down. When the US stopped building as many houses in 2005-06, it predicted the recession of 2007-08.

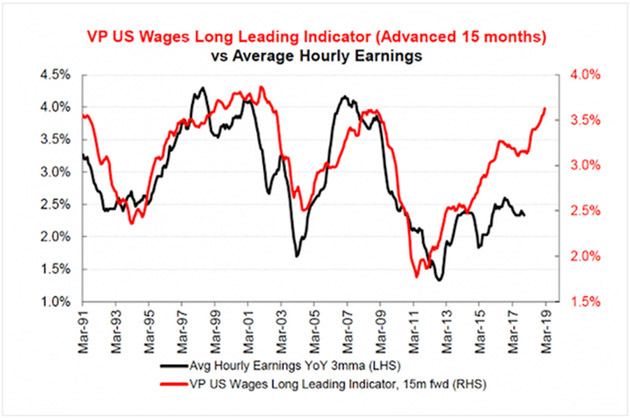

Our leading indicator for wages normally provides a 15 month advanced warning of changes in wages. It is pretty good and all the ingredients are the same ones that have accurately worked for decades, yet the relationship has broken down. It was annoying me: why are wages not following growth? I should know the answer to why this is happening. I should have all the tools, yet something appeared broken in the economy.

All the signs that should lead to higher wages are present. Today, employers are saying that it is hard to find workers and many small businesses say they expect to raise wages, initial unemployment claims are extremely low. This should be an economy that is good for workers to get higher wages, yet wages stink.

After a lot of research, I think the answers are clear. Let’s look at the problem.

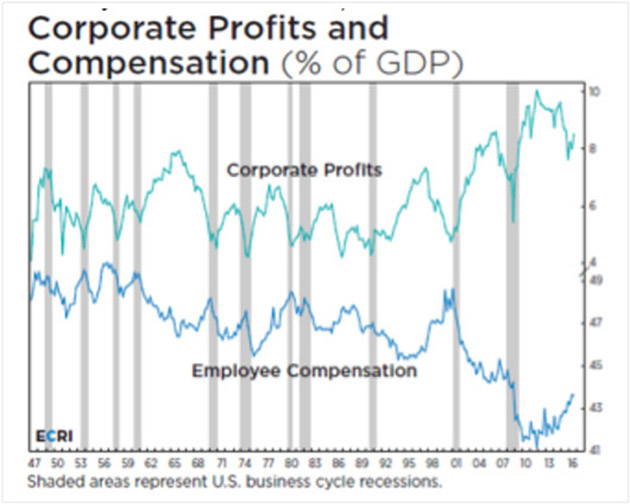

Companies are keeping more of the economic pie

The flipside of low wages is that companies have taken a record part of the economic pie. Corporate profits as percentage of Gross Domestic Profit (GDP) are near record highs and labor’s share of GDP is near record lows. You can see from the following chart that the chart looks like a giant alligator jaws. The divergence started in the early 1980s when the regular rise and fall of corporate profits and workers’ compensation broke down.

The trend in corporate profits is a mystery to economists and investment strategists. Jeremy Grantham, a well-known investor, has pointed out, “Profits are the most mean reverting series in finance. If margins don’t revert something has gone wrong with capitalism.”

Employee compensation as a percentage of GDP has been falling for years

(Source: Economic Cycle Research Institute)

Something has indeed gone very wrong with capitalism. In a competitive market, if a company is making a lot of money, other companies will get excited by the prospects of high profits and will enter the industry and compete. Eventually margins decline as more competitors fight each other. That is how dynamic, capitalist economies should be. Something is profoundly broken with capitalism if corporate profit margins do not revert to the historical mean.

Rising industrial concentration is a powerful reason why profits don’t mean revert and a powerful explanation for the imbalance between corporations and workers. Workers in many industries have fewer choices of employer, and when industries are monopolists or oligopolists, they have significant market power versus their employees.

The role of high industrial concentration on inequality is now becoming clear from dozens recent academic studies. Work by The Economist found that over the fifteen-year period from 1997 to 2012 two-thirds of American industries were more concentrated in the hands of a few firms.(i) In 2015, Jonathan Baker and Steven Salop found that “market power contributes to the development and perpetuation of inequality.”(ii)

One of the most comprehensive overviews available of increasing industrial concentration shows that we have seen a collapse in the number of publicly listed companies and a shift in power towards big companies. Gustavo Grullon, Yelena Larkin, and Roni Michaely have documented how despite a much larger economy, we have seen the number of listed firms fall by half, and many industries now have only a few big players. There is a strong and direct correlation between how few players there are in an industry and how high corporate profits are.(iii)

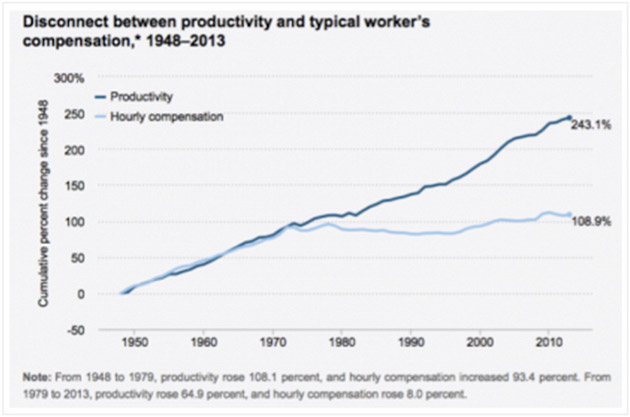

Workers are productive but are not getting paid for it

Given the gaping disparity in pay between the average worker and CEOs, you might imagine managers were superstars and the average worker was bad at his job. But that is hardly the case. While many executives go on the front cover of Fortune or Forbes and get all the credit for their company stock, worker productivity has been steadily rising for decades. Unfortunately, earnings have not kept up with productivity increases. Workers are producing more goods with less labor, and companies are making higher profits, but the benefits are not being shared with workers. Notice that productivity growth has been rising in a straight line since the 1950s, but starting in 1980 hourly compensation has not risen much. The money from that gap doesn’t vanish into thin air, and it has to show up somewhere.

Disconnect between productivity and typical worker’s compensation

(Source: Economic Policy Institute)

Some economists have argued that the gap between wages and productivity is an illusion. They argue that much of the gap can be explained by year-end bonuses, which are not included in hourly pay, by healthcare costs, which doesn’t show up in a paycheck but the worker benefits from, and by stock options, which also doesn’t show up in a paycheck. However, we can discount these explanations. Healthcare, bonuses and options are a real expense to companies, and if companies were getting hit with these costs instead of wages, it would show up in corporate profit margins. Today, corporate profit margins would not be at record highs. If the divergence between wages and productivity is real, the difference should clearly shows up in corporate profits, and it does.

Companies have more market power

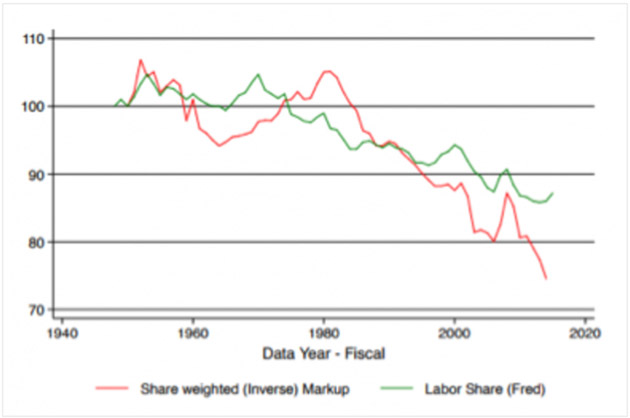

The economists Jan De Loecker of Princteon University and Jan Eeckhout of the University College London found that average markups, have surged since the early1980s. The average markup was 18% in 1980, but by 2014 it was nearly 70%. Higher markups suggest an increase in what economists refer to as “market power,” which is the result of more highly concentrated industries.

A markup may sound like a very technical term, but you see it in everyday life. The best example is in luxury goods, where the right logo on a handbag will make the leather sell for a lot more than it costs to make. Part of what you’re paying for is status and association.

De Loecker and Eechkhout noted that The rise in markups explains lower wages almost perfectly. They also found that “the rise in markups naturally gives rise to a decrease in the labor share, a decrease in the capital share, a decrease in low skilled wages, a decrease in labor market participation, and decrease in job flows.”(iv)

The Evolution of Average Markups (1960-2014)

(Source: Jan De Loecker, Jan Eeckhout)

Market power has been rising in many industries. Americans have the illusion of choice, but in industry after industry, a few players dominate the entire market:

- Two corporations control 90% of the beer Americans drink.

- When it comes to high-speed internet access, almost all markets are local monopolies; over 75 percent of households have no choice with only one provider.

- Four airlines completely dominate airline traffic, often enjoying local monopolies or duopolies in their regional hubs. Five banks control about half of the nation’s banking assets.

- Many states have health insurance markets where the top two insurers have 80-90% market share. For example, in Alabama one company has 84% market share and in Hawaii one has 65% market share.

- Four players control the entire US beef market.

- After two mergers this year, three companies will control 70 percent of the world’s pesticide market and 80 percent of the US corn-seed market.

The list of industries with dominant players is endless.

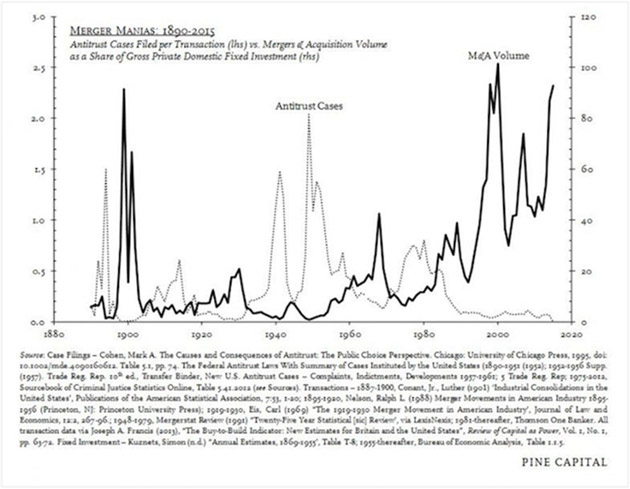

After a wave of mergers, there is simply less competition.

Merger Manias 1890-2015: Merger Waves Are More Frequent and Bigger

(Source: Pine Capital)

Over half of all public firms have disappeared over the last twenty years. We’ve seen a collapse of publicly listed companies. Astonishingly, according to a study by Credit Suisse, “between 1996 and 2016, the number of publicly-listed stocks in the U.S. fell by roughly 50%â—âfrom more than 7,300 to fewer than 3,600â—âwhile rising by about 50% in other developed nations.”(i) It is not lower growth or the global Financial Crisis that caused fewer IPOs. This is distinctly an American phenomenon.

The decline in listed companies has been so spectacular that the number lower is than it was in the early 1970s, when the real GDP in the US was just one third of what it is today.(ii) America’s economy grows ever year, but the number of listed companies shrinks. On this trend, by 2070 we will only have one company per industry.

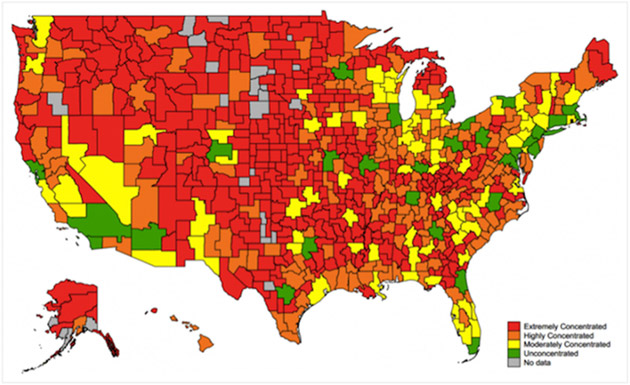

Many workers are dealing with a monopsonist

In a monopoly, there is only one seller, while in a monopsony, there is only one buyer. The extreme example of a monopsony is a coal town in West Virginia, where the only buyer of labor is the coal company

Large parts of America are dominated by monopsonies. In a comprehensive study, Marshall Steinbaum, Ioana Marinescu, and Jose Azar looked across all industries and commuting zones in the US to measure how concentrated employers were. They found that most labor markets are very concentrated and that it has a strong negative impact on posted wages for job openings.(v) They showed that going from a very competitive to a highly concentrated job market is associated with a 15-25% decline in wages.

The study shows that labor monopsony is not only pervasive across the US, but is especially so in non-metropolitan areas. This makes intuitive sense – smaller towns mean fewer employment options.

Areas with fewer employers have lower wages

(Source: Roosevelt Institute)

In a monopsony, workers have little choice in where they work and have little negotiating power for wages with employers. In a healthy economy, many firms would be competing equally for workers and would be incentivized to entice new hires with higher wages, better benefit packages, and few restrictions on their next career moves. But monopsonies make it easier for firms to depress worker wages. The classic example of this is a coal-mining town, where the coal plant is the only employer and only purchaser of labor. Today, in many smaller towns, WalMart is the new coal plant – and is the only retail company hiring.

Many firms are able to suppress the bargaining power of labor by making labor markets less competitive. Economists Jason Furman and Alan Krueger argue that firms in concentrated industries are able to suppress wages through collusion and non-compete agreements that cover 20% of American workers.(vi)

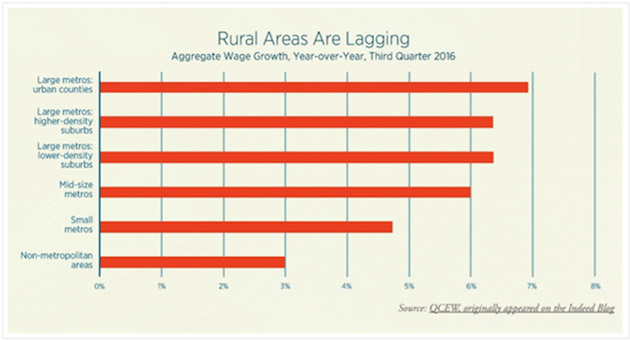

Many workers live in a rural area with less choice of jobs

Today, the story of America is largely the story of two economies – rural and urban. It was not always this way. The antitrust movement of the 1940s not only targeted giant firms, but was also an attempt to weaken regional centers that had amassed too much power. This largely worked and, by the mid 1970’s, there was a fairly uniform American standard of living – being middle class in the Mideast was pretty much the same as middle class in New England. However, in the 1980s, many of the policies that helped ensure this balance between regions was neglected or reversed.

A great divide formed between rural and metropolitan areas in the US. In 1980, if you lived in Washington D.C., your per-capita income was 29 percent above the average American; in 2013 you would be 68 percent above. In New York City, the income was 80 percent above the national average in 1980 and skyrocketed to 172 percent above by 2013.(vii) Power and money began concentrating in urban centers across the country as a rural ‘brain drain’ occurred.

Major cities attract diverse talent and many corporations, which must bid competitively for workers. Workers living in these cities make significantly more money than workers elsewhere. There is power in numbers, and nurses who have 5 metropolitan hospitals to choose from will make more money than those who work in a town with only one hospital.

Rural Areas Are Lagging

(Source: Bloomberg, Shift: The Commission on Work, Workers, and Technology)

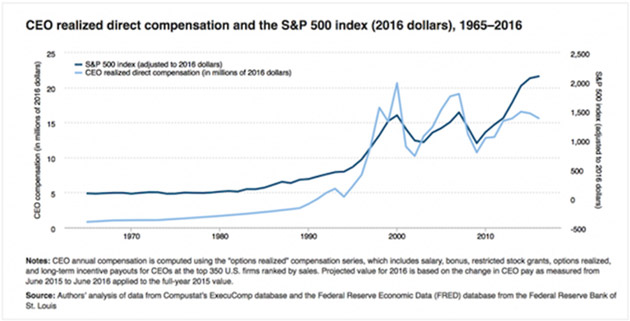

CEOs are getting paid a lot more than workers

In the US CEO pay has exploded. From 1978 to 2013, CEO compensation adjusted for inflation increased 937%. By contrast, the average worker’s income grew by a pathetic 10% over the same period. To put the change in perspective, the CEO-to-worker pay ratio was 33-to-1 in 1978 and grew to 276-to-1 in 2015.(viii) The US is a big outlier in terms of how vastly overpaid the top corporate officers are vs the average worker. For CEOs in the UK, the ratio is 22; in France, it’s 15; and in Germany it’s 12.(ix) US CEOs are vastly overpaid no matter how you look at it.

Rising CEO-to-Worker Compensation Ratio

(Source: Economic Policy Institute)

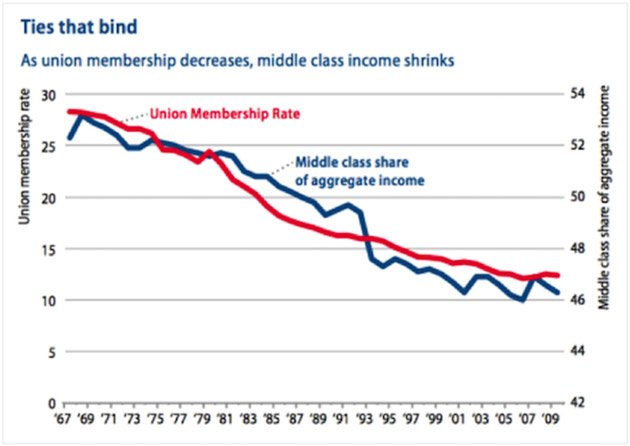

There is no countervailing force to high CEO and low worker pay

Unions maintained an important part in American working life for decades, but then declined again. In 1983, about 1 in 5 Americans were part of a union; today, only 6.4% of private sector workers in America are unionized and less than 11% of total workers.(x) This represents a considerable decline in the ability of workers to organize. Unions, though controversial, provided a needed forum for workers to band together and advocate for their collective rights.

Falling Union Membership and Lower Middle Class Share of Income

(Source: The Atlantic)

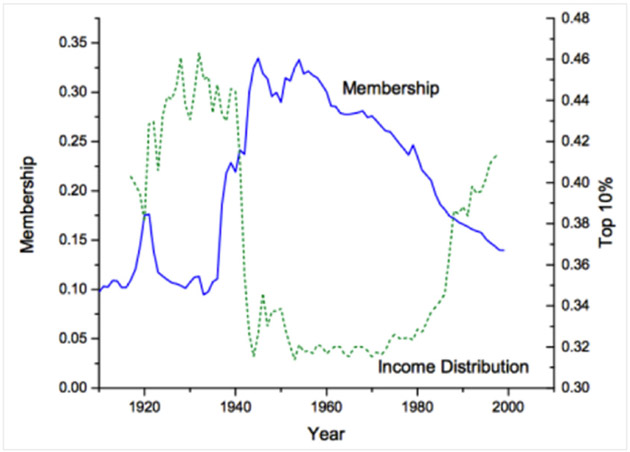

Inequality is inversely related to union membership. If you plot the percentage of national income going to the top 10%, as you can see it is almost the perfect mirror image. When union membership is low, a higher percentage of income goes to the top 10%. This may help, in part, to explain recent trends in income inequality.

Union Membership vs Income Distribution to Top 10%

(Source: The Atlantic, Emin M. Dinlersoz and Jeremy Greenwood) (xi)

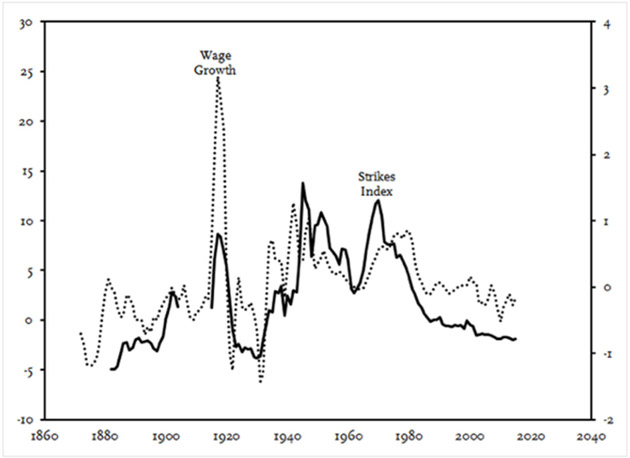

Managers collectively represent thousands if not millions of shareholders. Union leaders may likewise represent thousands if not millions of workers. The strength of unions, however, does not come merely from concentrating forces but from the real threat of strikes. There is an extremely high correlation historically between the index of the number of strikes in the US with the wage growth of workers. Today, strikes are extremely rare, and this in part explains why wages are so low.

Wage growth closely associated with strikes

(Source: Taylor Mann, Pine Advisors)

I’m writing a book on monopolies, monopsonies and how they are affecting startups, workers’ pay and economic growth. This is just a small part of some of the ideas in the book.

If you liked this post, let me know and I’ll keep you posted on further charts, blog posts and let you know when my book is coming out.

(ii) Baker, Jonathan and Salop, Steven, “Antitrust, Competition Policy, and Inequality” (2015). Working Papers. http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/fac_works_papers/41/

(iii) Grullon, Gustavo and Larkin, Yelena and Michaely, Roni, Are U.S. Industries Becoming More Concentrated? (August 31, 2017). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2612047

(iv) Jan De Loecker, Jan Eeckhout, “The Rise of Market Power and the Macroeconomic Implications”, (August 2017) NBER Working Paper No. 23687 http://www.nber.org/papers/w23687

(i) Credit Suisse, The Incredible Shrinking Universe of Stocks: The Causes and Consequences of Fewer U.S. Equities http://www.cmgwealth.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/document_1072753661.pdf

(ii) Grullon, Gustavo and Larkin, Yelena and Michaely, Roni, Are U.S. Industries Becoming More Concentrated? (August 31, 2017). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2612047

(v) http://rooseveltinstitute.org/how-widespread-labor-monopsony-some-new-results-suggest-its-pervasive/ and Azar, José and Marinescu, Ioana Elena and Steinbaum, Marshall, Labor Market Concentration (December 15, 2017). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3088767

(vi) Why Aren’t Americans Getting Raises? Blame the Monopsony, Jason Furman and Alan B. Krueger Wall Street Journal https://www.wsj.com/articles/why-arent-americans-getting-raises-blame-the-monopsony-1478215983

(vii) Longman, Phil. “Why the Economic Fates of America’s Cities Diverged.” Nov 28, 2015. https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2015/11/cities-economic-fates-diverge/417372/

(viii) http://www.epi.org/publication/ceo-pay-continues-to-rise/

(ix) http://work.chron.com/ceo-compensation-vs-world-15509.html

(x) Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Union Members Summary.” January 26, 2017. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/union2.nr0.htm

(xi) Ebersole, Phil. June 12, 2012. https://philebersole.wordpress.com/2012/06/12/the-decline-of-american-labor-unions/